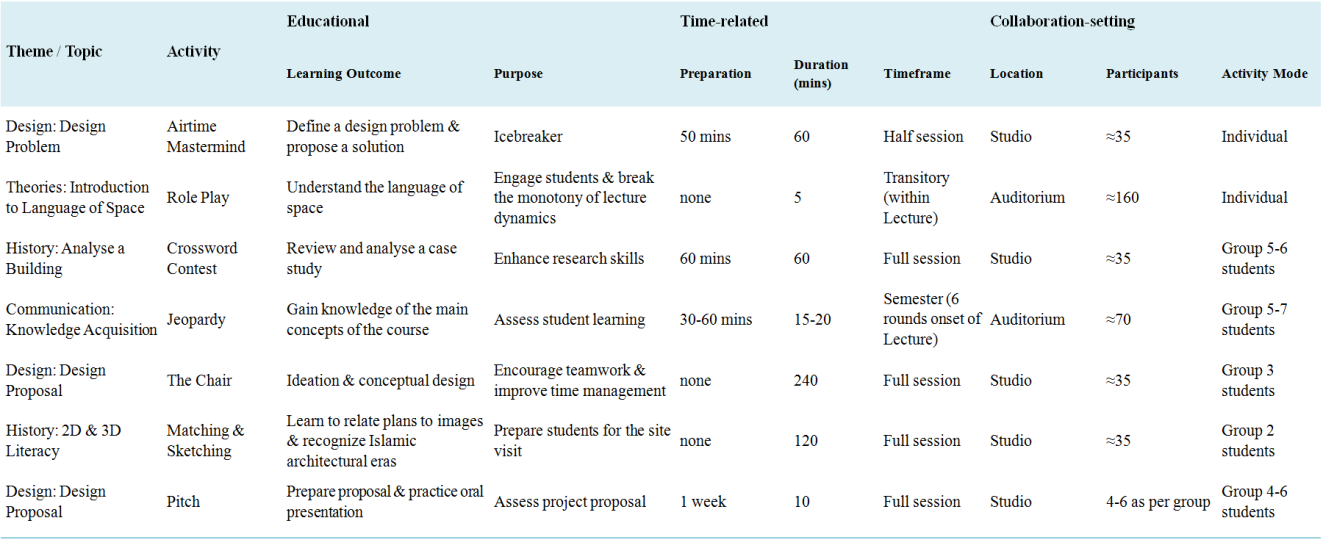

Millennials and post-millennials demand alternative educational models, leading educators to adopt Experiential Learning (ExL) theory, which acknowledges ludicity in learning spaces. ExL is the subject of a growing body of research to date. Gamification is recognized to enhance student engagement and academic success. This research aims to investigate gamified activities tailored to Interior Architecture and Design (IAD) education. An exploratory approach is used to review the potential of gamification as a tool to achieve ExL contributing to students’ learning experience. A literature review lays a foundation for ExL theory and gamification. Pilot ExL-based gamified activities conducted on year 1 IAD students at Coventry University - Egypt, are documented using thick description based on participant observations, which inform the potential and drawbacks of each gamified activity. Thematic analysis is conducted to attain the research findings. The findings are reviewed by two methods, superimposing the pilot gamified activities collectively on the ExL cycle to confirm students interacted with the four modes of the cycle. Second is by assessing the activities according to their design considerations including educational, time-related, collaboration-setting, and operational considerations. Findings subsequently yield guidelines for educators supporting the design of gamified activities. This is to aid IAD educators in establishing ExL by infusing their curricula with gamified activities matching the educational expectations and needs of today’s students, without diverting from desired content. Results reveal that there is a direct correlation between the effective planning of a gamified activity following the derived design considerations and the completion of the ExL cycle.

| Published in | International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications (Volume 10, Issue 2) |

| DOI | 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13 |

| Page(s) | 42-59 |

| Creative Commons |

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. |

| Copyright |

Copyright © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Science Publishing Group |

Interior Architecture Education, Interior Design Education, Experiential Learning, Gamification, Gamified Activities

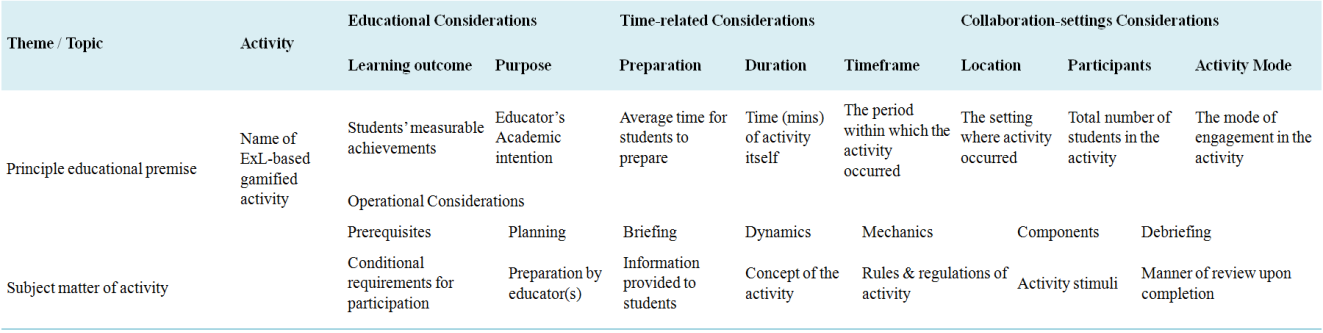

EDUCATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS | Learning outcomes – Set measurable learning outcomes. Then, plan and design the expected outputs accordingly to verify hitting the desired learning outcome. |

Purpose – Select the purpose in conjunction with the learning outcome(s) before designing the gamified activity. The purpose should be very specific to ensure its achievement. | |

TIME-RELATED CONSIDERATIONS | Preparation – Be aware of the type of preparation required. Controlled or no preparation ensures student participation, while uncontrolled preparation demands self-motivation, and therefore educators should plan it in an engaging manner to ensure effective participation. |

Duration – Ensure all participants are included in all stages of the activity in one way or another, even as they perform different tasks. For lengthy activities, educators need to split them into stages with intervals, while avoiding redundancy to reduce the duration and maintain students’ interest. | |

Time frame – Set the time frame according to the importance of the learning outcome and purpose. For example, icebreakers should not exceed a session, while activities that directly contribute to knowledge acquisition could be extended. | |

COLLABORATION-SETTINGS CONSIDERATIONS | Location – Be conscious when selecting the location of the gamified activity. A flexible spatial setup accommodates diverse gamified activities, allowing students to interact freely. |

Participants - Ensure that all participants are seen and heard. In case of large cohorts, the support of additional educators can facilitate the effective operation of the gamified activity. | |

Activity mode – Select an activity mode that ensures that each participant has a clearly defined role in the gamified activity. | |

OPERATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS | Prerequisites – Define the needed prerequisite knowledge of the gamified activity to consciously situate it within the timeline of the course and link it with other courses if needed. |

Planning – Be aware that planning gamified activities is time-consuming. This includes designing the activity in addition to altering roles to assess its outcomes. Educators should enhance their skills and familiarity with the various platforms and applications appealing to today’s students. | |

Briefing – Provide a briefing to explain game dynamics, mechanics, and components to make sure students understand what is expected from them during the activity. | |

Dynamics – Design the activity dynamics ensuring it reflects the learning outcome while conveying interesting concepts and narratives to immerse students into the game mode. | |

Mechanics – Set clear rules that govern the activity to activate a gamified mode while ensuring the educational outputs are generated. | |

Components – Creatively select or make components that arouse students’ participation. Visuals and sounds along with competition components contribute to students' engagement. | |

Debriefing – Allocate adequate time for a debriefing. Educators should realise when to stop the activity to allow enough time for this reflection; as the debriefing is as important as the activity itself. |

IAD | Interior Architecture and Design |

CrE | Creative Exploration |

LoS | Language of Space |

ExL | Experiential Learning |

CE | Concrete Experience |

RO | Reflective Observation |

AC | Abstract Conceptualization |

AE | Active Experimentation |

| [1] | F. Hénard and D. Roseveare, "Fostering Quality Teaching in Higher Education: Policies and Practices. An IMHE guide for higher education institutions," OECD, 2012. |

| [2] | A. W. Bates, Teaching in a Digital Age: Guidelines for Designing Teaching and Learning, 2nd ed., BCcampus Open Publishing, 2019, pp. 101-110. [Online]. Available: |

| [3] | T. Hui, S. Lau and M. Yuen, "Active Learning as a Beyond-the-Classroom Strategy to Improve University Students' Career Adaptability," Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 11, 2021. |

| [4] |

J. Legény and R. Špaček, "Humour as a Device in Architectural Education," Global Journal of Engineering Education, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 6-13, January 2019. [Online]. Available:

http://www.wiete.com.au/journals/GJEE/Publish/vol21no1/01-Spacek-R.pdf#page=7.27 |

| [5] | U. B.-A. Ordu, "The Role of Teaching and Learning Aids/Methods in a Changing World," in New Challenges to Education: Lessons from around the World, vol. 12, Sofia: Bulgarian Comparative Education Society, BCES Conference Books, 2021, pp. 210-216. [Online]. Available: |

| [6] | D. A. Kolb, J. S. Osland and I. M. Rubin, The Organizational Behavior Reader, Prentice-Hall, 1995. |

| [7] | J. Cantor, Experiential Learning in Higher Education: Linking Classroom and Community, Washington DC, 1997. |

| [8] | S. D. Wurdinger and J. A. Carlson, Teaching for Experiential Learning: Five Approaches that Work, R&L Education, 2009. |

| [9] |

FutureLearn, "What is Experiential Learning and How Does It Work?," 8 September 2021. [Online]. Available:

https://www.futurelearn.com/info/blog/what-is-experiential-learning |

| [10] |

IEL, "What is Experiential Learning?," 23 October 2023. [Online]. Available:

https://experientiallearninginstitute.org/what-is-experiential-learning/ |

| [11] | C. Dichev and D. Dicheva, "Gamifying Education: What is Known, What is Believed and What Remains Uncertain: A Critical Review," International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 14, 2017. |

| [12] | K. M. Kapp, The Gamification of Learning and Instruction: Gamed-based Methods and Strategies for Training and Education, 1st ed., San Fransisco: Pfeiffer, 2012. |

| [13] | B. G. Taÿçÿ, "Utilization of Digital Games in Built Environment Education," Universal Journal of Educational Research, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 632-637, 2016. |

| [14] | G. D. Askin, "Gamification of Design Process in Interior Architecture Education: Who? with Whom? Where? How?," in SHS Web of Conferences ERPA International Congresses on Education 2019 (ERPA 2019), 2019. |

| [15] |

H. Lei, Y. Cui and W. Zhou, "Relationships Between Student Engagement and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis," Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, vol. 46, no. 3, p. 517, 2018. [Online]. Available:

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A534100003/AONE?u=anon~3ee5a245&sid=googleScholar&xid=5477873b |

| [16] | A. Kolb and D. Kolb, 8 Things to Know about the Experiential Learning Cycle, Kaunakakai: EBLS Press, 2023. |

| [17] | I. E. Gencel, M. Erdogan, A. Y. Kolb and D. A. Kolb, "Rubric for Experiential Training," International Journal of Progressive Education, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 188-211, 2021. |

| [18] | M. Mineiro and C. D'Avila, "Ludicity: Conceptual Comprehension of Graduate Students in Education," Educacao e Pesquisa, vol. 45, 7 October 2019. |

| [19] | T. Babacan Çörekci, "Game-based Learning in Interior Architecture," Design and Technology Education: An International Journal, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 55-78, 2023. [Online]. Available: |

| [20] | J. Lean, J. Moizer, C. Derham, L. Strachan and Z. Bhuiyan, "Real World Learning: Simulation and Gaming," in Applied Pedagogies for Higher Education, D. Morley and M. Jamil, Eds., Palgrave Macmillan, Cham., 2021. |

| [21] | A. Y. Kolb and D. A. Kolb, "Learning Styles and Learning Spaces: A Review of the Multidisciplinary Application of Experiential Learning Theory in Higher Education," in Learning Styles and Learning, R. Sims and S. S. J., Eds., Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2006, pp. 45-91. |

| [22] | A. Y. Kolb and D. A. Kolb, The Experiential Educator: Principles and Practices of Experiential Learning, Kaunakakai, HI: EBLS Press, 2017. |

| [23] | D. A. Kolb, Experiential Learning: Experience as The Source of Learning and Development, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1984. |

| [24] | K. L. Stock and D. Kolb, "The Experiencing Scale: An Experiential Learning Gauge of Engagement in Learning," Experiential Learning & Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 4, 2021. |

| [25] | Merriam-Webster Dictionary, "Definition of GAMIFICATION," 13 April 2024. [Online]. Available: |

| [26] | S. Qiao, S. Yeung, Z. Zamzami, T. K. Ng and S. Chu, "Examining the Effects of Mixed and Non-Digital Gamification on Students' Learning Performance, Cognitive Engagement and Course Satisfaction," British Journal of Educational Technology., 2022. |

| [27] | I. Caponetto, J. Earp and M. Ott, "Gamification and Education: A Literature Review," in 8th European Conference on Games Based Learning, Germany, 2014. [Online]. Available: |

| [28] | R. P. Lopes, "Gamification as a Learning Tool," International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 565-574, September 2016. |

| [29] | M. Hughes and C. J. Lacy, "The Sugar’d Game before Thee": Gamification Revisited," Portal: Libraries and the Academy, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 311-326, 2016. |

| [30] | C. Beard, Experiential Learning Design: Theoretical Foundations and Effective Principles, 1st ed., New York: Routledge, 2022. |

| [31] | D. Kayımbaşıoğlu, B. Oktekin and H. Haci, "Integration of Gamification Technology in Education," in 12th International Conference on Application of Fuzzy Systems and Soft Computing, ICAFS, Vienna, Austria, 2016. |

| [32] | L. Stapley, "Introduction," in Experiential Learning in Organisations: Applications of the Tavistock Group Relations Approach, L. Gould, L. Stapley and M. Stein, Eds., London, Karnac Books, 2004, pp. 1-10. |

| [33] | M. A. Razali, N. Ismail and N. Hassim, "The Role of Experiential Learning in Creative Design Appreciation Among TDS Students at Taylor’s University," in 3rd International Conference on Creative Media, Design and Technology, 2018. |

| [34] | A. E. Kelly, "Theme Issue: The Role of Design in Educational Research," Educational Researcher, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 3-4, 2003. |

| [35] |

A. M. Panchariya, "Experiential Learning as a Backbone of Architecture Education," International Journal of Engineering Technology Research & Management IJETRM, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 33-38, 2018. [Online]. Available:

https://www.ijetrm.com/issues/files/Mar-2019-19-1552973251-4.PDF |

| [36] | K. R. Finckenhagen, "Context in Gamification: Contextual Factors and Successful Gamification," 2017. [Online]. Available: |

| [37] | M. Terras and E. Boyle, "Integrating Games as a Means to Develop E-Learning: Insights from a Psychological Perspective," British Journal of Educational Technology, vol. 50, no. 3, p. 1049–1059, 2019. |

| [38] | M. Romero and M. Usart, "Time Factor in the Curriculum Integration of Game-Based Learning," in New Pedagogical Approaches in Game Enhanced Learning: Curriculum Integration, 1st ed., S. de Freitas, M. Ott and M. M. Popescu, Eds., IGI Global, 2013. |

| [39] | A. Ahmad, F. Zeeshan, R. Marriam and A. Samreen, "Does One Size Fit All? Investigating the Effect of Group Size and Gamification on Learners’ Behaviors in Higher Education," Journal of Computing in Higher Education, p. 296–327, 2021. |

| [40] | R. Stake and M. Visse, "Case Study Research," in International Encyclopedia of Education, 4th ed., R. J. Tierney, F. Rizvi and K. Ercikan, Eds., Elsevier Science, 2023, pp. 85-91. |

| [41] | K. Musante (DeWalt), "Participant Observation," in Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology, Maryland, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, pp. 251-292. |

| [42] | S. J. Tracy, Qualitative Research Methods Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. |

| [43] | R. N. Aljabali and N. Ahmad, "A Review on Adopting Personalized Gamified Experience in the Learning Context," in IEEE Conference on e-Learning, e-Management and e-Services (IC3e), Langkawi, Malaysia, 2018. |

| [44] | D. Gray, "Airtime Mastermind," 6 August 2010. [Online]. Available: |

| [45] | D. Gray, "Forced Analogy," 27 January 2011. [Online]. Available: |

| [46] | M. Michalko, Thinkertoys A Handbook of Creative-Thinking Techniques, 2nd ed., Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2006. |

APA Style

Mehelmy, D. E., Zeini, I. E. (2024). Experiential Learning Through Gamification in Interior Architecture and Design. International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications, 10(2), 42-59. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13

ACS Style

Mehelmy, D. E.; Zeini, I. E. Experiential Learning Through Gamification in Interior Architecture and Design. Int. J. Archit. Arts Appl. 2024, 10(2), 42-59. doi: 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13

AMA Style

Mehelmy DE, Zeini IE. Experiential Learning Through Gamification in Interior Architecture and Design. Int J Archit Arts Appl. 2024;10(2):42-59. doi: 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13

@article{10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13,

author = {Dina El Mehelmy and Ingy El Zeini},

title = {Experiential Learning Through Gamification in Interior Architecture and Design

},

journal = {International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications},

volume = {10},

number = {2},

pages = {42-59},

doi = {10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13},

url = {https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13},

eprint = {https://article.sciencepublishinggroup.com/pdf/10.11648.j.ijaaa.20241002.13},

abstract = {Millennials and post-millennials demand alternative educational models, leading educators to adopt Experiential Learning (ExL) theory, which acknowledges ludicity in learning spaces. ExL is the subject of a growing body of research to date. Gamification is recognized to enhance student engagement and academic success. This research aims to investigate gamified activities tailored to Interior Architecture and Design (IAD) education. An exploratory approach is used to review the potential of gamification as a tool to achieve ExL contributing to students’ learning experience. A literature review lays a foundation for ExL theory and gamification. Pilot ExL-based gamified activities conducted on year 1 IAD students at Coventry University - Egypt, are documented using thick description based on participant observations, which inform the potential and drawbacks of each gamified activity. Thematic analysis is conducted to attain the research findings. The findings are reviewed by two methods, superimposing the pilot gamified activities collectively on the ExL cycle to confirm students interacted with the four modes of the cycle. Second is by assessing the activities according to their design considerations including educational, time-related, collaboration-setting, and operational considerations. Findings subsequently yield guidelines for educators supporting the design of gamified activities. This is to aid IAD educators in establishing ExL by infusing their curricula with gamified activities matching the educational expectations and needs of today’s students, without diverting from desired content. Results reveal that there is a direct correlation between the effective planning of a gamified activity following the derived design considerations and the completion of the ExL cycle.

},

year = {2024}

}

TY - JOUR T1 - Experiential Learning Through Gamification in Interior Architecture and Design AU - Dina El Mehelmy AU - Ingy El Zeini Y1 - 2024/06/06 PY - 2024 N1 - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13 DO - 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13 T2 - International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications JF - International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications JO - International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications SP - 42 EP - 59 PB - Science Publishing Group SN - 2472-1131 UR - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijaaa.20241002.13 AB - Millennials and post-millennials demand alternative educational models, leading educators to adopt Experiential Learning (ExL) theory, which acknowledges ludicity in learning spaces. ExL is the subject of a growing body of research to date. Gamification is recognized to enhance student engagement and academic success. This research aims to investigate gamified activities tailored to Interior Architecture and Design (IAD) education. An exploratory approach is used to review the potential of gamification as a tool to achieve ExL contributing to students’ learning experience. A literature review lays a foundation for ExL theory and gamification. Pilot ExL-based gamified activities conducted on year 1 IAD students at Coventry University - Egypt, are documented using thick description based on participant observations, which inform the potential and drawbacks of each gamified activity. Thematic analysis is conducted to attain the research findings. The findings are reviewed by two methods, superimposing the pilot gamified activities collectively on the ExL cycle to confirm students interacted with the four modes of the cycle. Second is by assessing the activities according to their design considerations including educational, time-related, collaboration-setting, and operational considerations. Findings subsequently yield guidelines for educators supporting the design of gamified activities. This is to aid IAD educators in establishing ExL by infusing their curricula with gamified activities matching the educational expectations and needs of today’s students, without diverting from desired content. Results reveal that there is a direct correlation between the effective planning of a gamified activity following the derived design considerations and the completion of the ExL cycle. VL - 10 IS - 2 ER -