3. A Corpus-based Methodology

This study uses the “V + Dào” construction as a case study to investigate the conceptual primitives underlying motion event distribution, focusing on both internal and external event integration. The research follows a systematic methodology, including data collection, coding, statistical analysis, and visualization.

3.1. Data Collection of “V + Dào” Construction

The initial step involves data selection based on three key criteria:

(1) Colloquial Style: The data must reflect spoken, natural language use, rather than literary or formal styles. (2) Frequency: The data should feature frequent occurrences in speech rather than rare or exceptional cases. (3) Pervasiveness: The data should represent a broad spectrum of semantic notions, rather than being limited to a narrow range

| [21] | Talmy, L. (1985). Lexicalization patterns: semantic structure in lexical forms. In T. Shopen (Ed.) Language Typology and Syntactic Description, vol. 3: Grammatical Categories and the Lexicon (pp. 36-149). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

[21]

. Accordingly, this study draws data from the “Spoken Language” section of the Center for Chinese Linguistics corpus at Peking University (CCL). The sources include transcriptions of the “Beijing Dialect Survey Data in 1982,” 21 dialogues from diverse mediums, and five TV interviews, such as “Dating with Lu Yu”.

After conducting data searches, verification, and refinement, 611 concordances (tokens) representing 143 categories (types) were identified as aligning with the motion event.

Figure 1 illustrates these results.

Figure 1. The structure and summary of “V + Dào” construction in motion events.

Figure 1 provides a detailed analysis of the 611 observations of “V + Dào” constructions identified as motion events. Within this framework, two variables related to the figure entity stand out. The agency of the figure entity (FigEnt_Agen) accounts for 515 occurrences, while the animacy of the figure entity (FigEnt_Anim) is even more prominent, with 567 instances. These high frequencies emphasize the central role of agency and animacy in shaping the motion event.

The ground entity (GroEnt) in these motion events is consistently identified as “space.” This singular categorization highlights its critical function as a defining element in construing the motion event’s trajectory. Meanwhile, the variable of activating process (ActiPro) is bifurcated into two distinct values: “motion,” which dominates with 576 occurrences, and “stationariness,” appearing 35 times. Correspondingly, these values align with the associating function (AssoFun), represented by “path” (frequency = 577) for motion and “site” (frequency = 35) for stationariness. Together, these variables provide a nuanced understanding of the dynamic and stationary aspects of motion events.

The supporting relation (SuppRel) introduces a greater level of complexity, encompassing nine distinct values: “cause,” “manner,” “path,” “concomitance,” “cause+manner,” “cause+path,” “manner+path,” “path+path,” and “figure+path.” This diversity reflects the intricate ways in which supplementary relations contribute to the elaboration and motivation of motion events. Additionally, the syntactic structure of the “V + Dào” construction (SynType_VD) is categorized into two types: “backward bound complements (BBC)” and “forward bound complements (FBC).”

Further analysis of the syntactic type of “X” (SynType_X) reveals three distinct values: a local noun (LocaN), which overwhelmingly accounts for 603 instances; a specific local clause (LocaC), observed only once; and non-text elements (NoT), appearing in seven instances. These findings underline the predominance of local nouns as syntactic complements in “V + Dào” constructions.

The internal event integration patterns of “V” (IEI_V) exhibit remarkable complexity, incorporating 12 distinct values, such as “motion+cause” and “motion+manner.” These patterns reflect diverse ways in which subevents are conflated within the verb. Similarly, the internal event integration patterns of “Dào” (IEI_D) are categorized into two values: “motion+path” and “stationariness+site.” This distinction captures the dual role of “Dào” in representing either movement or stationary location.

Finally, the verb-complement type (EEI_Type) for “V + Dào” constructions in motion events is identified as the verb-directional complement (VDir). This type encapsulates the structural and functional essence of the construction. Regarding the distribution of “V + Dào” constructions in concrete Chinese expressions (Chin_VD), 143 instances were documented.

Figure 2 illustrates their respective frequencies and proportions, offering further insight into their usage and variability in natural language contexts.

Figure 2. The pie chart of Chin_VD in motion events.

In

Figure 2, 143 Chinese expressions of “V + Dào” constructions as motion events are listed in a descending order aligned with their frequencies, among which the top ten frequent expressions are: “回到 (return to, frequency = 93)”, “来到(come to, frequency = 57)”, “跑到 (run to, frequency = 55)”, “走到 (walk to, frequency = 36)”, “送到 (send to, frequency = 20)”, “搬到(move to, frequency = 20)”, “带 (bring to, frequency = 14)”, “拉到 (pull to, frequency = 12)”, “赶到 (rush to, frequency = 10)”, and “运到 (transport to, frequency = 18)”. In accordance with the research questions of this study, “V + Dào” constructions of motion events will be further explored and discussed in terms of their event semantics, syntax properties, and event integration patterns.

Figure 2 presents a comprehensive list of 143 Chinese expressions formed by “V + Dào” constructions representing motion events, ranked in descending order of frequency. Among these, the ten most frequently occurring expressions are: “回到” (return to, frequency = 93), “来到” (come to, frequency = 57), “跑到” (run to, frequency = 55), “走到” (walk to, frequency = 36), “送到” (send to, frequency = 20), “搬到” (move to, frequency = 20), “带到” (bring to, frequency = 14), “拉到” (pull to, frequency = 12), “赶到” (rush to, frequency = 10), and “运到” (transport to, frequency = 18). These high-frequency expressions reflect the predominant patterns in how motion is linguistically conceptualized and expressed in Mandarin Chinese.

In line with the research objectives, these “V + Dào” constructions will be subjected to an in-depth analysis. This analysis focuses on three critical dimensions: the event semantics, which examines the meaning and components of the motion events; the syntactic properties, which explore the structural characteristics of the constructions; and the event integration patterns, which delve into the mechanisms of combining subevents within the construction. By systematically addressing these dimensions, the study aims to elucidate the linguistic and cognitive underpinnings of “V + Dào” constructions in motion events.

3.2. Data Encoding

The 611 concordances of “V + Dào” constructions are encoded comprehensively across three dimensions: event semantics, syntactic properties, and event integration patterns. Event semantics are analyzed through the lens of conceptual primitives outlined in macro-event theory. These are quantified with specific variables and their corresponding values. Special attention is given to the agency and animacy of the figural entity, which are evaluated for their potential correlations with the event integration patterns observed in the data. These correlations include variables such as the nature of the figural and ground entities, the process activation, association functions, support relations, and the macro-event types they instantiate.

The syntactic characterization of the “V + Dào” construction builds upon

| [1] | Chao, Y. R. (1968). A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. |

[1]

classification of verb complements into free complements, bound complements, and bound phase complements. In cases where “Dào” functions as a free complement, the verb (“V”) and complement (“Dào”) retain mutual independence, as seen in examples like “来到故乡” (have come to hometown), where both “来故乡” (come to hometown) and “到故乡” (arrive in hometown) are grammatical. Bound complements, however, exhibit interdependence, as illustrated by “碰到一件怪事” (have met a strange thing), where neither “*碰一件怪事” (*meet a strange thing) nor “*到一件怪事” (*arrive a strange thing) is acceptable. Bound phase complements present a hierarchy, with “Dào” subordinate to “V,” exemplified in “挣到钱” (has earned the money). Here, while “挣钱” (earn the money) is grammatical, “*到钱” (*arrive at the money) is not. Conversely, in some constructions, as Lyu

| [17] | Lyu, S. (1980). 800 Words in Modern Chinese. Beijing: Commercial Press. |

[17]

observes, “Dào” may assume the role of the main verb, subordinating “V,” such as in “走到张家” (walk to the Zhangs’), where “到张家” (arrive at the Zhangs’) is valid, but “*走张家” (*walk the Zhangs’) is ungrammatical. This nuanced interaction prompted the division of bound phase complements into forward bound complements and backward bound complements.

The syntactic properties of “X,” the complement following “Dào,” reveal significant variability. Building on the works of Lyu

| [17] | Lyu, S. (1980). 800 Words in Modern Chinese. Beijing: Commercial Press. |

[17]

and Zhu

| [29] | Zhu, D. (1982). Grammar Handouts. Beijing: Commercial Press. |

| [30] | Zhu, D. (1985). Grammar Discussions. Beijing: Commercial Press. |

[29, 30]

, “X” is shown to manifest as a noun, a clause, or even be omitted entirely. Nouns in this role can take locative forms, such as “家乡” (hometown) in “他回到了家乡” (he came back to his hometown), temporal forms, such as “明年暑假” (next summer vacation) in “等到明年暑假” (waiting until the next summer vacation), or patient forms, as in “你说的” (what you said) in “办得到你说的” (can achieve what you said). They may also appear as degree nouns, stimulus nouns, or others, depending on the specific context. Similarly, when “X” is realized as a clause, it may function as temporal, stimulus, locative, or patient, reflecting the intricate syntactic flexibility inherent in the construction. Additionally, “X” can manifest as an adjective, fulfilling roles such as stimulus, temporal, or degree markers.

From the perspective of event integration patterns, the analysis distinguishes between internal integration within “V” (IEI_V) and “Dào” (IEI_D) and external integration at the constructional level (EEI_VD). The latter encompasses broader semantic categories, including motion events, temporal contouring events, state change events, action correlating events, and realization events. The semantic typology of “V + Dào” constructions is further delineated into verb-directional (VDir), verb-resultative (VRes), and verb-phase (VPha) structures.

In summary, the encoding of the “V + Dào” construction encapsulates its complexity through three interrelated dimensions: event semantics, syntactic properties, and event integration patterns. This multi-faceted approach provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing the nuanced interplay between linguistic form and semantic function, as detailed in

Table 1.

Table 1. The tagging scheme of the “V + Dào” construction as Motion Event.

Three Levels | Variables | Values |

Event Semantics | Figural Entity (FigEnt) | Agentive (Agen) | [True]; [False] |

Animate (Anim) | [True]; [False] |

Ground Entity (GroEnt) | reference point in space [space] |

Activating Process (ActiPro) | [motion]; [stationariness] |

Association Function (AssoFun) | [path]; [site] |

Support Relation (SuppRel) | [precursion]; [enablement]; [cause]; [manner]; [subsequence]; [constitutedness] |

Syntactic Properties | Syntactic Types of “V + Dào” (SynType_VD) | Free Complements (FC); Forward Bound Complements (FBC); Backward Bound Complements (BBC); Bound Complements (BC) |

Syntactic Types of the Following Component “X” (SynType_X) | temporal nouns (TempN); locative nouns (LocaN); patient nouns (PtienN); stimulus nouns (StimuN); degree nouns (DgreN); temp oral clauses (TempC); stimulus clauses (StimuC); degree clauses (DgreC); patient clauses (PtienC); temporal adjectives (TempA); degree adjectives (DgreA); stimulus adjectives (StimuA); non-texts (NoT) |

|

Event Integration Patterns | Internal Event Integration (IEI) | “V” (IEI_V) | [Activating Process] + [Support Relation] (such as “[motion] + [cause]”) |

“Dào” (IEI_D) | [Activating Process] + [Association Function] (such as “[motion] + [path]”) |

External Event Integration (EEI) | The Types of Verb-complement Construction (EEI_Type) | Verb-Directional construction (VDir); Verb-Resultative construction (VRes); Verb-Phase construction (VPha) |

The data coding of the “V + Dào” construction, as outlined in

Table 1, encompasses three key dimensions: event semantics, syntactic properties, and event integration patterns. Each of these levels is defined by a set of variables and their corresponding values. While some of these variables function independently, others exhibit interdependencies. Specifically, within the realm of syntactic properties, the variables are independent of one another, allowing for a straightforward categorization. However, at the level of event integration patterns, the variables are not entirely independent; they are interconnected in ways that reflect the complex relationships between different aspects of the construction. These interrelations will be further explored in Section 4, where a deeper analysis of their interactions will be provided.

3.3. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

To conduct the statistical analysis, the annotated data for the "V + Dào" constructions, as previously described, was input into the R programming environment. Most of the data was converted from strings to factors using the "stringsAsFactors" function within the R code. In this section, two computational methods are employed: (1) correlation analysis using linear regression modeling and (2) statistical visualization through the "ggplo:" R package. The first method aims to compute the relationships between different variables, identifying their interactions, while the second method visualizes these interactions by displaying the correlation coefficients. Specifically, the R packages "ggplot2," "energy," and "car" are utilized to compute and visualize the correlation coefficients

| [9] | Levshina, N. (2015). How to do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis. Amsterdam/Plhiladelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. |

[9]

. Given that the relationships between the variables in our data are non-linear yet monotonic, non-parametric correlation statistics, such as Spearman’s ρ (‘rho’) and Kendall’s τ (‘tau’)

| [9] | Levshina, N. (2015). How to do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis. Amsterdam/Plhiladelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. |

[9]

, are employed. According to Levshina

| [9] | Levshina, N. (2015). How to do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis. Amsterdam/Plhiladelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. |

[9]

. a correlation is considered strong if the coefficient is greater than or equal to 0.7 or less than or equal to -0.7, moderate if it falls between 0.3 and 0.7 or between -0.3 and -0.7, and weak if it ranges from 0 to 0.3 or from 0 to -0.3. The detailed distributions of the "V + Dào" constructions and the correlation data across each variable are discussed further in Section 4.

4. Results and Analysis

In alignment with the research design of this study, the analysis of "V + Dào" constructions, specifically those involving action-correlating events, will be conducted through a comprehensive exploration of their event semantics, syntactic properties, and event integration patterns. This approach aims to provide a detailed understanding of the structural and functional aspects of these constructions within the context of event-related language use.

4.1. Event Semantics of “V + Dào” Constructions as Motion Events

In order to have a full view of the semantic properties of “V+Dao” constructions, we will take 6 variables into consideration – agency of the figural entity (FigEnt_Agen), animacy of the figural entity (FigEnt_Anim), ground entity (GroEnt), activating process (ActiPro), association function (AssoFun), and supporting relation (SuppRel). As the ground entity only contains one value of “space”, it can be left aside and will not be calculated in the data.

First of all, the agency and animacy features of figural entities (i.e. FigEnt_Agen and FigEnt_Anim) in motion events are summarized in

Table 2.

Table 2. Agency and animacy features of figure entities in motion events.

| FigEnt_Anim |

FigEnt_Agen | FALSE | TRUE | Total |

FALSE | 39 | 58 | 97 (16%) |

TRUE | 6 | 508 | 514 (84%) |

Total | 45 (7%) | 566 (93%) | 611 (100%) |

In

Table 2, we find that both FigEnt_Agen and FigEnt_Anim are true values in most circumstances, and the occasion with the lowest frequency is that the FigEnt_Anim is false while the FigEnt_Agen is true. The following examples respectively refer to the four combinations between FigEnt_Agen and FigEnt_Anim.

(3) 我冲到排练厅。

wǒ chōng dào pái liàn tīng

I rush arrive rehearsal room

I rushed to the rehearsal room.

(4) 一个飞弹打到电塔上。

yī gè fēi dàn dǎ dào diàn tǎ shàng

a missile shoot arrive the tower up

A missile was shot to the tower.

(5) 韩非子作为韩国的使者派到秦国。

Han Feizi zuò wéi hán guó de shǐ zhě pài dào qín guó

Han Feizi as Han Country’s envoy sent arrive Qin Country

Han Feizi, as an envoy in Han Country, was sent to Qin Country.

(6) 民企出走到外企。

mín qǐ chū zǒu dào wài qǐ

The private enterprises out go arrive foreign companies

The private enterprises go out / leave to the foreign companies.

The figural entities in the above instances are listed as “我(I)” in (3), “一个飞弹(a missile)” in (4), “韩非子(Han Feizi)” in (5), and “民企(the private enterprises)” in (6). “我(I)” in (3) and “民企(the private enterprises)” in (6) are agents or performers of actions represented by the motion verbs like “冲(rush)” and “出走(leave)”. “一个飞弹(a missile)” in (4) and “韩非子(Han Feizi)” in (5) are patients of the actions represented by the motion verbs of “打(shoot)” and “派(send)”. Besides, the figural entity “我(I)” is both agentive and animate, “一个飞弹(a missile)” is both non-agentive and inanimate, “韩非子(Han Feizi)” is non-agentive but animate, and “民企(the private enterprises)” is agentive but inanimate. Example (4) and (5) are also taken as middle constructions by some Chinese scholars. Thus, the figural entities of “一个飞弹(a missile)” and “韩非子(Han Feizi)” are, in fact, the patients of action verbs in the motion events. In other words, they are in the position of subjects in sentences, but they are non-agentive in semantics. Moreover, the former is inanimate, but the latter is animate. In example (6), the figural entity “民企(the private enterprises)” seems like a metonymical expression since it designates the people in “民企(the private enterprises)”, thus it is agentive but inanimate.

As only two values, true and false, are involved in the variables of the agentive and animate in figural entities (which are represented by FigEnt_Agen and FigEnt_Anim). The correlation coefficient shows that there does exist a moderate correlation between FigEnt_Agen and FigEnt_Anim (t=0.55, p<0.01). However, when calculating their relationships with Chin_VD, no relationship exists either between FigEnt_Agen and Chin_VD (t=0.01, p>0.05) or between FigEnt_Anim and Chin_VD (t=-0.02, p>0.05).

Secondly, concerning the variables of ActiPro and AssoFun, since they correspond to each other, we can analyze their corresponded values together. In a broad sense, motion events can be described by means of translational motion events and non-translational stationary events

| [22] | Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics: Typology and Process in Concept (Vol. 2). Cambridge: The MIT Press. |

[22]

. Therefore, the variables of ActiPro and AssoFun subsume the values of the motion/path and the stationariness/site, which are distributed in

Table 3.

Table 3. The distribution of activating processes and association functions in motion events.

ActiPro/AssoFun | Motion/Path | Stationariness/Site | total |

Frequency | 576 | 35 | 611 |

Percentage | 94% | 6% | 100% |

As

Table 3 indicates, the motion in ActiPro and the path in AssFun are the most frequent values in motion events. As noticed by

| [11] | Li, F. (2013). Two systemic errors in macro-event research. Foreign Languages in China, (2): 25-33. |

[11]

, too much attention has been paid to the translational motion events, but the non-translational stationary events are less focused on. Therefore, the corpus-based method can be a great help for us to obtain some relevant examples of translational motion events and non-translational stationary events.

(7) 我跑到井冈山了。

wǒ pǎo dào jǐng gāng shān le

I run arrive Jinggangshan city Asp.

I have run to Jinggangshan city.

(8) 你的女儿整天就趴到窗台上。

nǐ de nǚ ér zhěng tiān jiù pā dào chuāng tái shàng

your daughter all day just lie on the windowsill up

Your daughter lies on the windowsill all day.

Example (7) refers to the translational motion events, indicating somebody moves from somewhere to Jinggangshan city. In contrast, example (8) signifies the non-translational stationary event, for the agent in it is just staying at the windowsill with the manner of lying.

In

Table 3, we can find that the translational motion events account for a larger proportion than the non-translational stationary event in the data. The top ten translational motion verbs of “V + Dào” constructions are listed as follows: “回到(return to, frequency = 93)”, “来到(come to, frequency = 57)”, “跑到(run to, frequency = 55)”, “走到(walk to, frequency = 36)”, “送到(send to, frequency = 20)”, “搬到(move to, frequency = 20)”, “带到(bring to, frequency = 14)”, “拉到(pull to, frequency = 12)”, “赶到(rush to, frequency = 10)”, “打到(hit to, frequency = 9)”, “运到(transport to, frequency = 9)”. Meanwhile, the top ten the non-translational stationary verbs of “V + Dào” constructions are: “放到(put to, frequency = 6)”, “搁到(put aside to, frequency = 6)”, “坐到(sit to, frequency = 6)”, “站到(stand to, frequency = 5)”, “住到(live in, frequency = 2)”, “戴到(wear to, frequency = 2)”, “安到(fix to, frequency = 2)”, “留到(stay to, frequency = 1)”, “趴到(lie prone to, frequency = 1)”, “停到(stop to, frequency = 1)”, “安置到(fix up to, frequency = 1)”, “靠到(lean to, frequency = 1)”, “躺到(lie to, frequency = 1)”. When calculating the correlation coefficient between AssoPro and AssoFun, as expected, they are fully correlated with each other (t=1, p<0.01). In detail, if the activating process is the motion, its association function is supposed to be the path; and if the activating process is the stationariness, its association function is supposed to be the site. However, the correlation coefficient between AssoPro/AssoFun and Chin_VD is rather weak (t=-0.15, p<0.05). In other words, the distribution of “V + Dào” construction is not sensitive to the distribution of its activating process and association function in motion events.

Finally, the variable of SuppRel involves conceptual primitives conflated in “V” of the “V + Dào” construction. There are 9 values of SuppRel in motion events – “cause”, “cause+path”, “manner”, “manner+path”, “path”, “path+path”, and “subsequence”. Their distribution is represented in

Table 4 with regard to their frequencies, and this is visualized in

Figure 3 in terms of a pie chart.

Table 4. The distribution of support relations in motion events.

SuppRel | Frequency | Percentage |

manner | 256 | 41.99% |

cause | 165 | 26.96% |

path | 165 | 26.96% |

cause+path | 10 | 1.63% |

path+path | 4 | 0.65% |

manner+path | 4 | 0.65% |

concomitance | 3 | 0.49% |

subsequence | 3 | 0.49% |

figure+manner | 1 | 0.16% |

Total | 612 | 100.00% |

Figure 3. The pie chart of support relations in motion events.

The results in

Table 4 and

Figure 3 indicate that the values of the cause and the manner account for the most frequencies and proportions in motion events. However, apart from the subsequence that is conflated in “V” of “V + Dào” constructions, some situations with lower frequencies are not discussed by Talmy, including “path”, “path+path”, “cause+path”, “manner+path”. See example (9) to (17).

(9) 野鸡飞到饭锅里。

yě jī fēi dào fàn guō lǐ

the pheasant fly arrive the rice pot

The pheasant flew into the rice pot.

(10) 李小月来到华侨大厦。

Li Xiaoyue lái dào huá qiáo dà shà

Li Xiaoyue come arrive the Overseas Chinese building

Li Xiaoyue came to the Overseas Chinese building.

(11) 他被分配到北京市。

tā bèi fèn pèi dào běi jīng shì

he BEI assign arrive Beijing

He was assigned to Beijing.

(12) 她有10块钱掉到水沟里。

tā yǒu 10kuài qián diào dào shuǐ gōu lǐ

She had 10 RMB fall arrive ditch inside

She had her 10 RMB fallen into the ditch.

In example (9), the support relation (SuppRel) in “飞到(fly to)” is the manner, for the pheasant moves into the rice pot with the manner of “飞(fly)”. In example (10), the SuppRel in the verb “来(come)” is the path, but it is different from the path in the verb “到(arrive)”. Specifically speaking, the verb “来(come)” is a “deictic component” of the path

| [22] | Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics: Typology and Process in Concept (Vol. 2). Cambridge: The MIT Press. |

[22]

, but the verb “到(arrive)” is an “arrival vector” of the path

| [22] | Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics: Typology and Process in Concept (Vol. 2). Cambridge: The MIT Press. |

[22]

. In example (11), the SuppRel in “分配到(assign to)” is the cause, for he is forced to move to Beijing by the “cause” of the verb “分配(assign)”. In example (12), the verb “掉(fall)” conflates the traversal vector of the path and the cause in which the gravity of 10 RMB causes the money to fall into the ditch. Apart from the verb of “掉(fall)”, some motion verbs, such as “买(buy)” and “卖(sell)”, can also conflate the cause and the deictic component of the path in the process of conceptualization.

(13) 姐俩出来到河边。

jiě liǎng chū lái dào hé biān

two sisters out come arrive the river

The two sisters come out to the river.

(14) 净士宗走入到民间。

Jìng Shìzōng zǒu rù dào mín jiān

Jìng Shìzōng (the emperor) walk enter the people

The emperor walked into the people.

In example (13), since the complex verb of “出来(come out)” conflates the traversal vector of the path in “出(out)” and the deictic component of the path in “来(come)”, the value of SuppRel in “出来(come out)” refers to the pattern of “path+path”. Similarly, “走入(walk into)” in example (14) is also a complex verb, which conflates the manner in “走(into)” and the traversal vector of the path in “入(enter)”. On this account, the complex verbs in the position of “V” in “V + Dào” constructions can conflate more support relations.

(15) 张柏芝从北京哭到上海。

Zhang Baizhi cóng běi jīng kū dào shàng hǎi

Zhang Baizhi from Beijing cry arrive Shanghai

Zhang Baizhi cried to Shanghai from Beijing.

Example (15) is a specific case. In the movement from Beijing to Shanghai, the verb “哭(cry)”, in fact, does not express the motion ostensively. However, when “哭(cry)” and “到(to)” are fused together, the motion subevent in the verb “哭(cry)” will be activated and selected in representing a broader motion event together with the motion subevent of the verb “到(arrive)”. Since “哭(cry)” also expresses a concomitant subevent that indicates a specific and prominent action in the motion event, it can conflate the subevents of the motion and the concomitant in the verb “哭(cry)” of the “哭到(cry to)” construction. As indicated in Chapter 1, we find “哭到(cry to)” is similar to “cry along”, both the motion and the concomitance are conflated in the verb “cry”. Apart from “哭到(cry to)”, some similar examples in our data are “杀到了天津(killed to Tianjin)” and “修到洛邑(mend to Luoyi)”. In the former example, the concomitant subevent of the SuppRel is “killing (people)”, which lasts throughout the whole movement to Tianjin; in the latter example, the concomitant subevent of the SuppRel is “mending (a road)”, which sustains throughout the whole movement to Luoyi.

(16) 哨位报告到排指挥所。

shào wèi bào gào dào pái zhǐ huī suǒ

the sentry report arrive the platoon headquarters

The sentry reported to the platoon headquarters.

In instance (16), the SuppRel in “报告到(report to)” is a subsequent subevent. Only after accomplishing the movement to the platoon headquarters, can the sentry report what he wants to report. Similarly, when Talmy

| [22] | Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics: Typology and Process in Concept (Vol. 2). Cambridge: The MIT Press. |

[22]

analyzes the sentence “they locked the prisoner into his cell”, he explains that they should move the prisoner into his cell at first, and then the prisoner’s cell will be locked.

(17) 有人把唾液啐到我的左脸上。

yǒu rén bǎ tuò yè cuì dào wǒ de zuǒ liǎn shàng

somebody BA the saliva spit arrive my left face up

Somebody spat his/her saliva into my left face.

The verb “啐(spat)” in example (17) means that somebody puts forth his/her strength to spit out certain amount of the liquid in the mouth such as the saliva. In this sense, the verb “啐(spat)” in “啐到(spit to)” not only expresses the manner of the action, but also contains the figure of the motion event, even though the figure of “唾液(the saliva)” is strengthened outside the verb in example (17). We can also say “他啐了我一脸(he spat into all my face)” without this figure (i.e. the saliva) in spoken Chinese, for it is supposed to have been already conflated in the verb “啐(spat)”. Talmy

| [22] | Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics: Typology and Process in Concept (Vol. 2). Cambridge: The MIT Press. |

[22]

has a similar example, “I spat into the cuspidor”, and he illustrates that this kind of pattern with the figure conflated in the verb is quite characteristic in English. As a matter of fact, however, Atsugewi and a Hokan language of northern California also have plenty of examples of this type. Different from English, the verb “啐(spat)” in Chinese also expresses the conceptual primitive of the manner, that is, “putting one’s strength to spit out”. Therefore, the value of SuppRel in “啐(spat)” of “啐到(spit into)” forms the pattern of “figure+manner”.

Even though the frequencies are very low in the patterns of “cause+path”, “path+path”, “manner+path”, “subsequence”, “concomitance” and “figure+manner”, they still deserve being further explored. In addition, the relationship between the SuppRel and the distribution of Chin_VD is effective and significant (t=-0.2, p<0.01).

All the mentioned above pertains to the event semantics of motion events, and we find that the distribution of “V + Dào” construction is only weakly sensitive to the distribution of the support relation (SuppRel), but not to the agency and animacy in the figural entity (FigEnt_Agen & FigEnt_Anim), the activating process (ActiPro), and the association function (AssoFun).

4.2. Syntactic Properties of “V + Dào” Constructions as Motion Events

Section 4.1 has surveyed the variables in the event semantics of “V + Dào” constructions, and in this section, we’ll discuss two variables which are involved in the syntactic properties of the “(V + Dào) + X” constructions as motion events, specifically, the syntactic types of “V + Dào” construction (SynType_VD) and syntactic types of “X” (SynType_X). The variable of SynType_VD subsumes 2 values – FC (free complements) and BBC (backward bound complements). Meanwhile, the variable of SynType_X contains 3 values – the local noun, the local clause (LocaC), and the nontext (NoT, which means the SynType_X is omitted).

Table 5 and

Figure 4 reveals the distribution and visualization of their relationships.

Table 5. The distribution of syntactic properties in motion events.

| SynType_X |

SynType_VD | LocaN | NoT | LocaC | Total |

FC | 505 | 7 | 0 | 513 |

BBC | 98 | 0 | 0 | 98 |

Total | 603 | 7 | 1 | 611 |

Figure 4. The line chart of syntactic properties in motion events.

Based on

Table 5 and

Figure 4, we can learn that the value of FC (free complements) in SynType_VD accounts for the highest frequency in the data, and the value of LocaN (local noun) in SynType_X is the most frequent in motion events. No matter whether the value of SynType_VD is FC or BBC in motion events, we can learn that “Dào” in “V + Dào” constructions can be used as an independent verb.

As for the variable of SynType_VD, on the one hand, we can discern more detailed syntactic properties from the following examples.

(18) 我来到台湾。

wǒ lái dào tái wān

I come arrive Taiwan

I came to Taiwan.

(19) 太太走到地窖。

tài tài zǒu dào dì jiào

the lady walk arrive the basement

The lady walked to the basement.

(20) 我们把松鼠放到笼子里。

wǒ men bǎ sōng shǔ fàng dào lóng zǐ lǐ

we BA the squirrel put arrive the cage

We put the squirrel in the cage.

In example (18), the SynType_VD is FC, for both “我来台湾(I come to Taiwan)” and “我到台湾(I arrive in Taiwan)” are acceptable and grammatical in spoken Chinese. Different from example (18), example (19) cannot be substituted by the expression of “*太太走地窖(*the lady walked the basement)”, but “太太到地窖(the lady arrived at the basement)” is acceptable and grammatical in spoken Chinese. Thus, “*走地窖(*walked the basement)” is illegitimate without the verb “到(arrive)” in the phrase “太太走到地窖(the lady walked to the basement)”, and the SynType_VD in example (19)is BBC. One possible explanation may be that most motion or stationary verbs in the FC of SynType_VD are transitive verbs, but those in the BBC of SynType_VD are intransitive verbs. Example (20), to some extent, is similar to example (18), in which we can say “放笼子里(put in the cage)” and “到笼子里(arrive at the cage)”. However, when we put “放到(put in)” into a BA construction, we can only say “我们把松鼠放放笼子里(we put the squirrel in the cage)” but not “*我们把松鼠到笼子里(*we take the squirrel arrive at the cage)”. Since “松鼠到笼子里(the squirrel arrives at the cage)” is still grammatical without the BA construction, the SynType_VD in this situation is still considered as being annotated as the value of FC.

On the other hand, concerning the variable of SynType_X, its distributions in the above instances are all locative nouns, such as the locative noun of “台湾(Taiwan)” in (18), “地窖(the basement)” in (19), and “笼子里(in the cage)” in (20). Nevertheless, sometimes the SynType_X can be omitted such as in example (19). In some specific occasions, the SynType_X can also be a local clause, such as “就是这个楼(it is this building)” as in example (22).

(21) 给他送到, 由亲朋好友给他送到坟地。

gěi tā sòng dào, yóu qīn péng yǒu gěi tā sòng dào fén dì

for him send arrive, by his family and friends GEI him send arrive the graveyard

Sending him to, he was sent to the graveyard by his family and friends.

(22) 给我带到就是这个楼。

gěi wǒ dài dào jiù shì zhè gè lóu

GEI me bring arrive it is this building

It is this building that I was brought to.

In example (21), even though SynType_X is omitted in the first clause of the sentence, it can be explained in the second clause in spoken Chinese, that is, “送到坟地(send to the graveyard)”. Example (21) also indicates that both of “V” and “Dào” together are often taken as a “minimal phonological group”

| [8] | Jiang, T. (1982). On the compounds of verbs and prepositions. Journal of Anhui Normal University, (1), 77-88. |

[8]

. Moreover, the value of SynType_X in example (22) refers to a local clause (LocaC), which mostly occurs in spoken Chinese. When example (22) is translated into English, it will become an inversion sentence, that is, “it is this building that I was brought to”.

When calculating the correlation coefficient between SynType_VD/SynType_X and the distribution of “V + Dào” construction in motion events, the distribution of “V + Dào” constructions is only moderately sensitive to the distribution of SynType_VD (t=-0.1, p<0.01), but not sensitive to the distribution of SynType_X (t=0.02, p>0.05).

The event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions as motion events have been discussed in Section 4.3, and we can roughly conclude that the distribution of “V + Dào” construction is only weakly correlated to the variables of SuppRel and SynType_VD.

4.3. Event Integration Patterns of “V + Dào” Constructions as Motion Events

In this Section, we continue to discuss the event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions and their correlations with regard to their semantics and syntactic properties. As proposed above, event integration can be interpreted in terms of the internal and external event integration. The former only occurs either in “V” or in “Dào” of the “V + Dào” construction, and the latter exists between “V” and “Dào” of the “V + Dào” construction. On this account, the discussion of the internal event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions should take the variables of IEI_V and IEI_D into consideration. Meanwhile, the external event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions tend to be related to the variables of Chin_VD, EEI_VD, and EEI_Type. Even though we have classified EEI_VD in terms of Talmy’s five macro-event types in general, it is still necessary to figure out how IEI_V and IEI_D are integrated as EEI_VD in detail.

Firstly, we will identify and discuss the variable of IEI_V. It contains 12 values, and each value conflates two variables of ActiPro and SuppRel. From example (9) to (17), IEI_V contains 9 values in motion events, which are represented by “motion+manner” in (9), “motion+path” in (10), “motion+cause” in (11), “motion+cause+path” in (12), “motion+manner+path” in [(13), “motion+path+path” in (14), “motion+concomitance” in (15), “motion+subsequence” in (16), and “motion+figure+manner” in (17). The additional 3 values of IEI_V pertains to stationary events, which can be represented respectively by the values of “stationariness+cause”, “stationariness+manner” and “stationariness+subsequence” in the following examples.

(23) 布的衣服都放到一边了。

bù de yī fú dōu fàng dào yī biān le

the fabric clothes all put arrive aside Asp

The fabric clothes were all put aside.

(24) 你站在楼顶上。

nǐ zhàn zài lóu dǐng shàng

you stand arrive the roof up

You stand on the roof.

(25) 逼他住到修道院。

bī tā zhù dào xiū dào yuan

force his live arrive the monastery

Force him to live in the monastery.

In example (23), the figural entity of “布的衣服(the fabric clothes)” is located aside somewhere by the cause of “放(put)”, and “你(you)” in example (24) stays on the roof with the manner of “站(stand)”. Moreover, example (25) is rather specific, for “他(he)” is forced to live in the monastery, which is a subsequent subevent after his being forced to move to the monastery. All of these examples, together with the previous (9) to (17), can be taken as the different internal event integration patterns in the verbs of “V + Dào” constructions (i.e. IEI_V). In a nutshell,

Table 6 and

Figure 5 provide us with the detailed distribution of IEI_V.

Table 6. The distribution of IEI_V in motion events.

IEI_V | Frequency | Percentage | Examples |

motion+manner | 246 | 40.36% | 野鸡飞到饭锅里。 (The pheasant flew into the rice pot.) |

motion+path | 164 | 26.80% | 李小月来到华侨大厦。 (Li Xiaoyue came to the Overseas Chinese building.) |

motion+cause | 143 | 23.37% | 他被分配到北京市。 (He was assigned to Beijing.) |

stationariness+cause | 20 | 3.27% | 布的衣服都放到一边了。 (The fabric clothes were all put aside.) |

stationariness+manner | 13 | 2.12% | 你站到楼顶上。 (You stand on the roof.) |

motion+cause+path | 10 | 1.63% | 她有10块钱掉到水沟里。 (She had her 10 RMB fallen into the ditch.) |

motion+path+path | 4 | 0.65% | 姐俩出来到河边。 (The two sisters come out to the river.) |

motion+manner+path | 4 | 0.65% | 净士宗走入到民间。 (Jìng Shìzōng (the emperor) walk enter the people.) |

motion+concomitance | 3 | 0.49% | 张柏芝从北京哭到上海。 (Zhāng Bǎizhī cried to Shanghai from Beijing.) |

stationariness+subsequence | 2 | 0.33% | 逼他住到修道院。 (Force him to live in the monastery) |

motion+figure+manner | 1 | 0.16% | 有人把唾液啐到我的左脸上。 (Somebody spat his/her saliva at my left face. ) |

motion+subsequence | 1 | 0.16% | 哨位报告到排指挥所。 (The sentry reported to the platoon headquarters.) |

Total | 612 | 100% | |

Figure 5. The bar chart of IEI_V in motion events.

In

Table 6 and

Figure 5, IEI_V has various internal event integration patterns. As Yu & Li

| [24] | Yu, L. & F., Li. (2018). An event integration approach to the variation of “V + Dào” construction in verb complement typology. Foreign Languages and Their Teaching, (1), 72-83. |

[24]

suggest, the internal event integrations patterns in IEI_V of “V + Dào” constructions involve alternate combinations of conceptual primitives, which are listed as follows.

1) IEI_V can conflate the values in the variables of Actipro and SuppRel. For instance, “飞(fly)” conflates the conceptual primitives of the motion and the manner (i.e. motion+manner), and “分配(assign)” encodes the motion and the cause (i.e. motion+cause).

2) IEI_V can conflate the values in the variables of ActiPro and AssoFun. For example, “来(come)” integrates the conceptual primitives of the motion and the path (i.e. motion+path).

3) IEI_V can conflate the values in the variables of ActiPro, SuppRel and AssoFun. For instance, “掉(fall)” includes the conceptual primitives of the motion, the cause, and the path (i.e. motion+cause+path).

4) IEI_V can conflate one value in ActiPro and two values in AssoFun. For example, “出来(come out)” conflates the motion, the traversal vector of the path and the deictic components of the path (i.e. motion+path+path).

5) IEI_V can conflate the values in the variables of ActiPro, FigEnt, and SuppRel. For instance, “啐(spit)” contains the conceptual primitives of the motion, the figure and the manner (i.e. motion+figure+manner).

To make a format of these internal event integration patterns of IEI_V, some of them can be formatted as “2” where two conceptual primitives are conflated, and some can be numbered as “3” in which three conceptual primitives are integrated. See the summaries in

Table 7 and

Figure 6.

Table 7. The formats and the distribution of IEI_V in motion events.

Formats | IEI_V | Frequency | Total |

2 (Two conceptual primitives are conflated in IEI_V) | motion+manner | 246 | 592 (97%) |

motion+path | 164 |

motion+cause | 143 |

motion+concomitance | 3 |

motion+subsequence | 1 |

stationariness+cause | 20 |

stationariness+manner | 13 |

stationariness+subsequence | 2 |

3 (Three conceptual primitives are conflated in IEI_V) | motion+cause+path | 10 | 19 (3%) |

motion+path+path | 4 |

motion+manner+path | 4 |

motion+figure+manner | 1 |

Total | 12 | 611 | 611 (100%) |

Figure 6. The surface chart of IEI_V in motion events.

In

Table 7 and

Figure 6, different from Talmy’s (2000b) macro-event theory, IEI_V can encode not only 2 conceptual primitives, such as “motion+manner”, but also 3 conceptual primitives, such as “motion+path+path”. On this account, these 12 event integration patterns in the variable of IEI_V can be categorized into two groups. One group consists of 2 conceptual primitives, and the other contains 3 conceptual primitives.

Secondly, the variable of IEI_D conflates 2 values in the variables of Actipro and AssoFun. They are, namely, “motion+path” (frequency = 576) and “stationariness+site” (frequency = 35) (see

Figure 1). Different from the English satellites in the motion events, “Dào”, as the directional verb, is not subordinate to the previous verb of “V” in the “V + Dào” construction. In this sense, “Dào” can conflate the conceptual primitives in the variables of Actipro and AssoFun, for “Dào” per se can be used as an independent verb to express the motion event. Diachronically, “Dào” can be used independently as a verb since the archaic Chinese, hence this syntactic property still remains in expressing the motion event in modern Chinese. In this sense, the internal event integration patterns in IEI_D can be abstracted and formulated as “2”, which means there are two conceptual primitives conflated in IEI_D.

Thirdly, the variable of EEI_VD, as the external event integration of “V + Dào” constructions, is based on the formation between IEI_V and IEI_D. We can see how the variables of IEI_V and IEI_D can be combined at first, and then discuss how they are fused together in our event integration model.

Table 8 shows us the various event integration patterns of EEI_VD in motion events.

Table 8. The formats and the distribution of EEI_VD in motion events.

Formats | EEI_VD | Frequency | Total |

2+2 | (motion+manner)+(motion+path) | 246 | 592 (97%) |

(motion+path)+(motion+path) | 164 |

(motion+cause)+(motion+path) | 143 |

(motion+concomitance)+(motion+path) | 3 |

(motion+subsequence)+(motion+path) | 1 |

(stationariness+cause)+(stationariness+site) | 20 |

(stationariness+manner)+(stationariness+site) | 13 |

(stationariness+subsequence)+(stationariness+site) | 2 |

3+2 | (motion+cause+path)+(motion+path) | 10 | 19 (3%) |

(motion+path+path)+(motion+path) | 4 |

(motion+manner+path)+(motion+path) | 4 |

(motion+figure+manner)+(motion+path) | 1 |

Total | 12 | 611 | 611 (100%) |

In

Table 8, EEI_VD has 12 external event integration patterns based on the combinations of IEI_V and IEI_D. The relation between them can be abstracted and formulated as two kinds of formats – one is “2+2”, and the other “3+2”. Among these external event integration patterns, we can find that both IEI_V and IEI_D can conflate the same conceptual primitive of “motion” in the variable of ActiPro, which can be taken as the conceptual mapping between IEI_V and IEI_D, which functions as the basis of their fusion. In addition, it is the conceptual overlap that integrates IEI_V and IEI_D together. Each of them can provide a conceptual slot for each other. For instance, when “走(walk)” and “到(arrive)” are fused together as a “V + Dào” construction of “走到(walk to)”, in their “2+2” format of “(motion+manner) + (motion+path)”, the conceptual primitive of “motion” is selected as the mapping basis for fusing “走(walk)” and “到(arrive)” together. Moreover, the verb “走(walk)” can provide a conceptual slot of the path that is filled by the verb “到(arrive)”. In return, the verb “到(arrive)” can supply a conceptual slot of the manner that is filled by the verb “走(walk)”. In this sense, the slots in “走(walk)” and “到(arrive)” are mutually overlapped by each other. Therefore, “走(walk)” and “到(the arrival vector of the path)” are integrated and fused together by means of conceptual mapping and conceptual overlap.

Finally, the last variable in the external event integration is EEI_Type, which has only one value – verb-directional construction (VDir). Since the variable of EEI_Type with one value cannot be taken into the correlation analysis, we assume that almost all “V + Dào” constructions in motion events are verb directional constructions (VDir).

When calculating correlation coefficients between IEI_V / IEI_D and Chin_VD in motion events, the distribution of “V + Dào” structure is weakly sensitive to the distribution of IEI_V (t=-0.2, p<0.01), but not sensitive to the distribution of IEI_D (t=-0.05, p>0.05). It’s evident that the distribution of IEI_V is strongly influenced by the distribution of SuppRel, for the correlation coefficient is strong between them (t=0.8, p<0.01). Moreover, the correlation also exists between IEI_V and SynType_VD (t=0.23, p<0.01), IEI_V and IEI_D (t=0.4, p<0.01).

In Section 5.1, we have surveyed “V + Dào” constructions as motion events in terms of three levels – event semantics, syntactic properties, and event integration patterns. In accordance with the research questions of event integration patterns and their correlations, some preliminary conclusions can be drawn from two aspects as in the following.

1)The first aspect relates to the event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions in motion events. As the theoretical framework indicates, the internal event integration pertains to the variables of IEI_V and IEI_D, and the external event integration relates to the variable of EEI_VD and EEI_Type. Based on the discussion above, we find that:

a. IEI_V can conflate 2 conceptual primitives or 3 conceptual primitives (see Appendix I);

b. IEI_D can integrate 2 conceptual primitives, one is “motion+path” and the other is “stationariness+site”;

c. EEI_VD subsumes 12 external event integration patterns that can be formatted as “2+2” or “3+2”, in which IEI_V and IEI_D can be fused together by means of the shared conceptual primitive, such as the motion or the stationariness, and they can also provide the conceptual slots for each other;

d. The value of EEI_Type signifiers the verb-directional construction (VDir).

2)The second aspect pertains to the correlations between the event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions and their semantic/syntactic properties in motion events. In the internal event integration, we will take IEI_V and IEI_D into the correlation analysis with other variables; and in the external event integration, since there is only one value in EEI_VD and EEI_Type that cannot be used in correlation analysis, we can only take the variable of Chin_VD into the correlation analysis with other variables. Based on the correlation analysis in R programming and some research results discussed above,

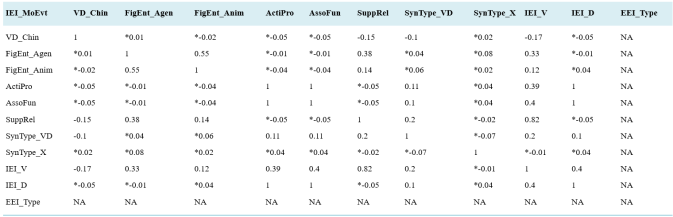

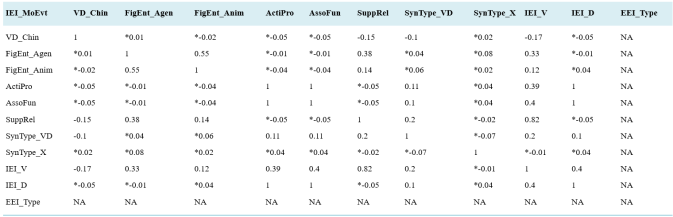

Table 9 reveals all the correlation coefficients among the variables of “V + Dào” constructions in motion events.

In

Table 9, the distribution of IEI_V is sensitive to the variables of FigEnt_Agen, FigEnt_Anim, ActiPro, AssoFun and SuppRel in event semantics, SynType_VD in syntactic properties, and IEI_D in the event integration patterns. According to the rule of thumb in the correlation coefficients

| [9] | Levshina, N. (2015). How to do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis. Amsterdam/Plhiladelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. |

[9]

, only the variable of SuppRel is strongly correlated. Meanwhile, the variables of IEI_D, AssoFun and ActiPro are moderately correlated, and the variables of FigEnt_Agen, SynType_VD and FigEnt_Anim are weakly correlated. A correlation hierarchy can be established as “(SuppRel) > (IEI_D > AssoFun > ActiPro) > (FigEnt_Agen > SynType_VD > FigEnt_Anim)”, and this can be visualized as in

Figure 7.

Figure 7. The visualization of the correlations between the variables and IEI_V in motion events.

In

Figure 7, since IEI_V consists of the variables of SuppRel and ActiPro, we find IEI_V is strongly correlated with SuppRel, but moderately correlated with ActiPro. In addition, IEI_V is also moderately sensitive to IEI_D and AssoFun, which means that IEI_V and IEI_D are mutually correlated with each other. In other words, the event integration does exist between the subevents in “V” and the subevents of “Dào” in “V + Dào” constructions. Moreover, IEI_V is weakly correlated with the agency and the animacy properties of the figural entities, for motion events can be expressed either by an agentive figure or a non-agentive figure or else expressed by an animate figure or an inanimate figure. For example, “滚下(roll down)” can be expressed by the sentence of “我把球滚下山 (I rolled the ball down the hill)” or by the sentence of “球滚下山(the ball rolled down the hill)”.

As for the variable of IEI_D, it is highly correlated to ActiPro and AssoFun in event semantics, moderately correlated to SynType_X in syntactic properties, and weakly correlated to IEI_V in the external event integration patterns. Their correlation hierarchy can be listed as “(AssoFun > ActiPro) > (IEI_V) > (SynType_X)”, and it is visualized in

Figure 8.

In the external event integration, the variable of Chin_VD is only weakly correlated to the variables of SuppRel, SynType_VD and IEI_V, and the correlation hierarchy is listed as “IEI_V > SynType_VD > SuppRel” and visualized in

Figure 9.

As can be seen from

Figures 7-9, not all variables are involved in the event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions, but the involved variables will exhibit different degrees of correlation coefficients in the event integration patterns of “V + Dào” constructions.

Figure 8. The visualization of the correlations between the variables and IEI_D in motion events.

Figure 9. The visualization of the correlations between the variables and Chin_VD in motion events.